Battery Pack Design for IC+ Electric Racing Motorbike

The IC+ is a student built electric racing motorcycle. It is designed to race the Isle of Man TT Zero event, a zero emission motorcycle race that promotes green technology. In 2013, the IC+ completed the TT Zero event for the first time, finishing 7th out of 8 with an average speed of 72 miles per hour. With the news that a new motor would be donated to the team from GKN EVO Electric, the focus of the team shifted to redesigning the bike around the new motor and reaching an average speed of 100 mph. A major part of this redesign was creating a new battery pack to support the motor.

Many tasks had to be carried out in order to create a fully working battery pack. Brand new battery cells had to be selected and purchased, a cooling analysis had to be done to determine the need of cooling systems in the battery pack, and the battery pack had to be designed to be waterproof, electrically insulated, easily maintained, and structurally sound. The pack had to be manufactured, assembled, and wired, tested in small and large scales for viability and performance, and integrated with a battery management system (BMS).

Our first task was to select a motor controller, which would determine the voltage range of our battery pack. Three choices were recommended to us by our industry sponsor, and we decided on the Rinehart PM100DX, mainly for space reasons. Our next task was to choose the appropriate battery cells for the pack. The team used a target energy capacity of 14kWh, based off an analysis of the TT course using data from the old bike and scaled up to our new average speed. In order to reach this energy in the space limitations of the bike, we required cells with a high energy density that could be packaged efficiently.

We finally selected Xalt Energy 53Ah LiPo pouch cells. To verify our selection, the battery specifications were used in a simulation of the race. The program calculated that a minimum of 66 batteries were required to stay above the lower voltage limit of the motor controller by the end of the race. The program also helped us estimate the heat generation within the cells. We found that in order to stay within the safe temperature limits of the battery with an appropriate safety margin, we required 74 cells. This number became our target number of cells to package into the bike. This analysis also gave us the confidence that battery cooling would not be required for our pack.

With our batteries selected, we then had to design the physical structure of our battery package. We decided on creating a modular pack, allowing easier maintenance of cells and quick assembly of the pack. We spent a lot of time analyzing the limited space available to us, using CAD models and physical mock ups to visualize the space. Space had to be negotiated from other parts of the bike in order to make room for all the cells. We also needed to design a frame that would house the modules and mount to the bike.

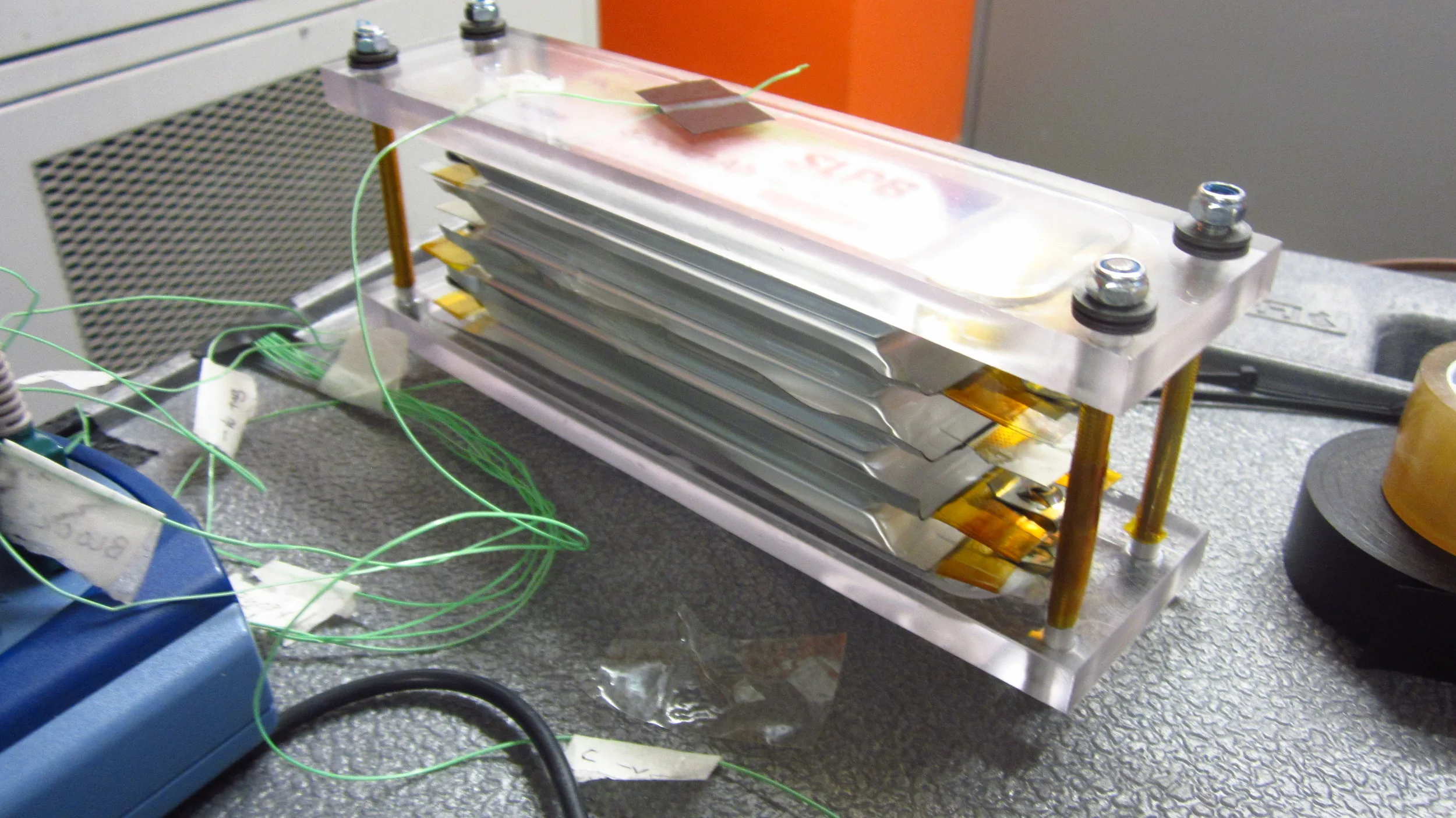

After many weeks iterating through several designs, we finally decided on module made up of a stack of cells that were clamped between two polycarbonate plates. The compressive force on the batteries would prevent damage of the wirings due to vibrations. The modules would then be mounted to a frame that would be made out of laser cut sheets of aluminum and steel. Finite element analysis helped us determine the material strength and thickness required for the frame. We also validated our frame design by creating a small section of the frame and performing a visual inspection of its deflection under loading from a prototype module. We also validated the manufacturing and assembly of our design through the prototypes.

We were unsure whether compression on the batteries would cause an adverse affect, therefore we designed several tests on similar batteries to validate our module design. We preformed vibration tests on a small prototype module and found that the batteries did not shift when subjected to typical road frequencies. We also performed electrical tests on clamped cells. Our tests found that the clamped cell performed better than the unclamped cell due to a reduction in the internal resistance of the battery, therefore decreasing the heat generation in the battery. There was still a possibility that successive loading and unloading on the battery could damage it in the long term.

Although by the end of the project, we were not able to build the entire battery package, we did create a solid foundation for the design. There is still some work left to be done, some testing and refinements on the design, considerations on wiring and waterproofing, and some adjustments to the frame. However, there is a good possibility for the pack to be fully constructed by the end of the next year.

Team Members

- Christian Behm

- Pawel Przytarski

- Ahlad Reddy

- Yan Zhao

- Chris Holdsworth-Swan (IC+ Team Leader)

- Professor Shawn Crofton (Advisor)

- Professor Greg Offer (Advisor)